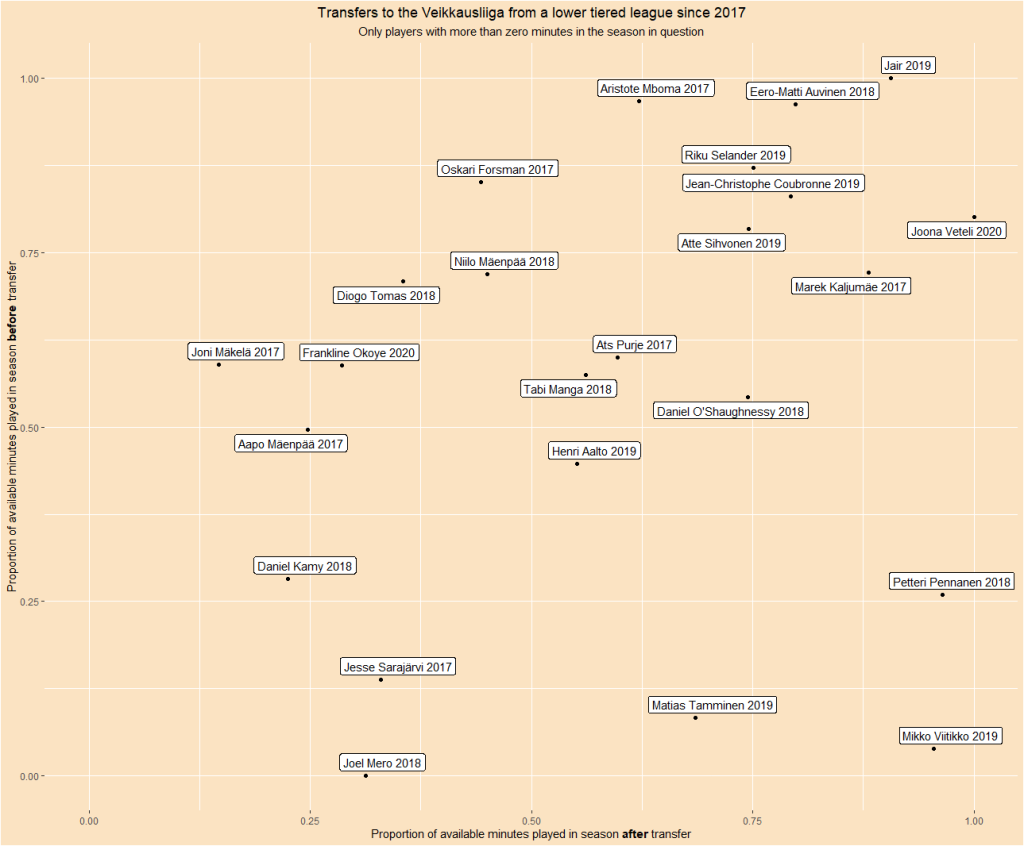

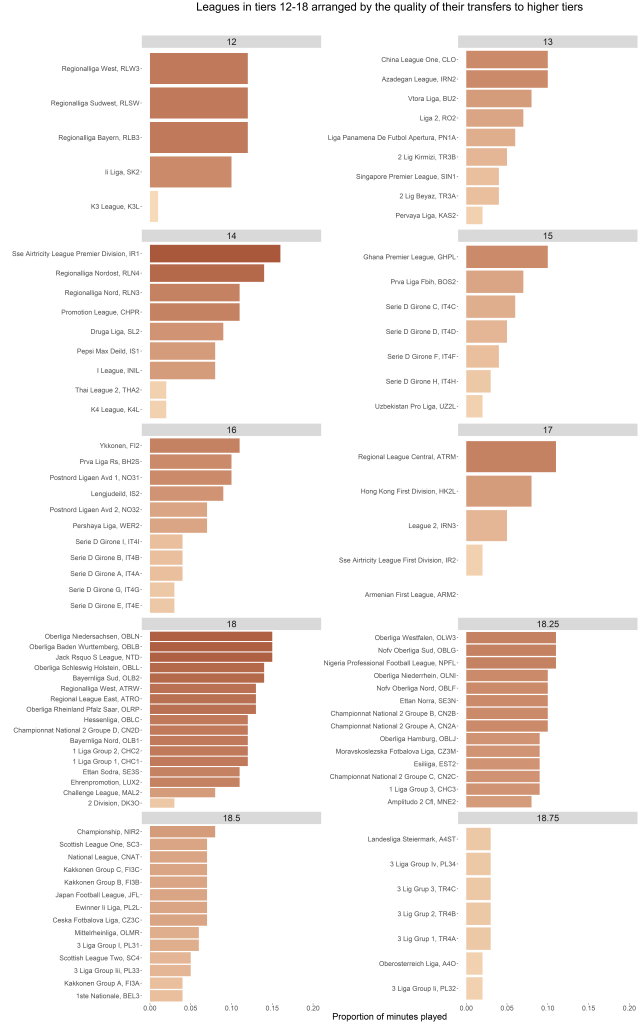

A couple of weeks back, I started as blog series on developing data driven recruitment practices on a miniscule budget. In the first part, I used data from Transfermarkt to produce a rough league tiering system, and then checked some transfer trends between these tiers to identify potential target markets for a Veikkausliiga team.

The end result was a list of low tiered leagues with a tendency to produce a comparatively high rate of successful transfers to higher tier leagues, including the German lower tiers, the Dutch third tier, the second and third tiers in Norway and Sweden as well as the Irish league. I also decided to include a couple of North American leagues, USL Championship and USL League One as well as the Canadian Premier League, because there has been a growing trend of movement to these leagues from the Veikkausliiga, and I think Finnish teams would do well to look to these growing leagues for value. In the same vein, I am also sort of interested in the English non-league and the Baltic leagues, as there are quite a few people working in Finnish football who will have ready made networks in these types of places, allowing for potentially smoother business. I also included the Japanese and South Korean lower tiers, because one of the premises of Minor League Scouting is that if you’re looking for value on the market, you need to be able to provide some kind of non-monetary value back to the player you’re interested in. East Asia (specifically Japan) is a place with a strange cultural bond to Finland, which might make it easier to convince players to move here. There is already some evidence of this in the successful transfer of Atomu Tanaka to HJK as well as some of the Japanese players that have joined Ykkönen teams in the recent past, most notably Taiki Kagayama, but also some of the players currently plying their trade there.

In this part of the series, we’re going to look at some tools for evaluating players, as well as for quickly surveying larger amounts of data. This will be done through a couple of real-life scenarios from this season. To do this, we’re going to use Wyscout data for a couple of reasons. First, Wyscout is one of the resources that most every team are using by default (InStat being the other), so, at least in theory, using their product for something like this would add nothing to the running costs of a hypothetical team. Second, Wyscout, despite not really having too many more advanced tools for playing with data, at least in the version I am using, gives you the option of exporting stats to Excel (at the player or team level). By creating a scraper that utilizes this function, you can (slowly) gather quite a vast amount of player-match level data from a large array of leagues, allowing you to build the data exploration tools yourself. For this blog, this is quite handy, as it’ll allow us to make player comparisons across leagues with very little hassle.

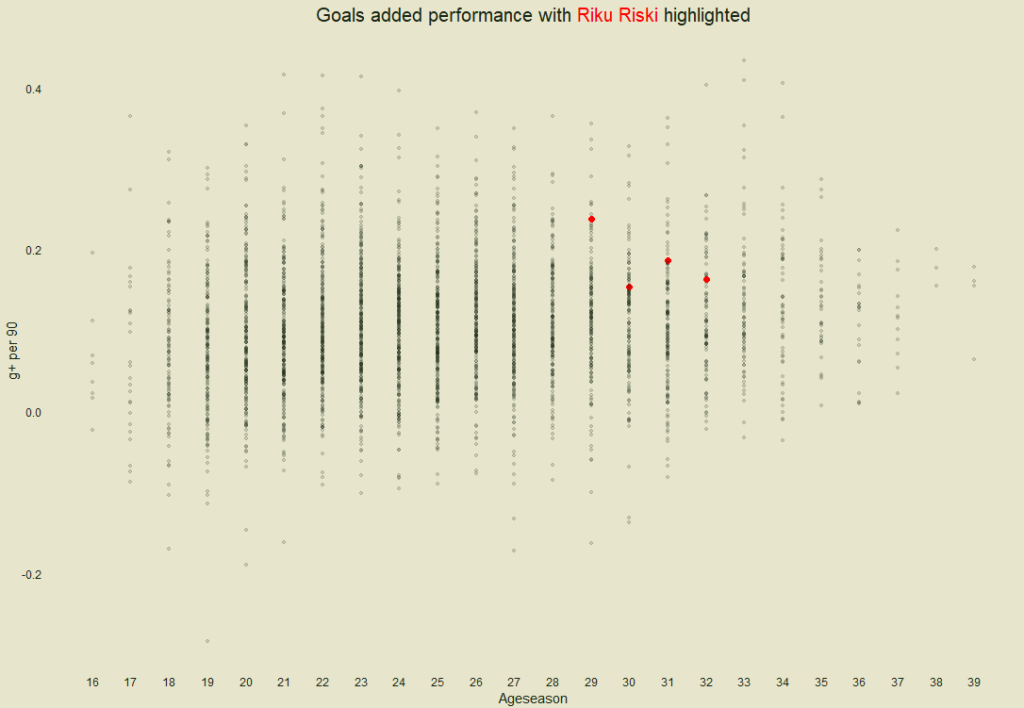

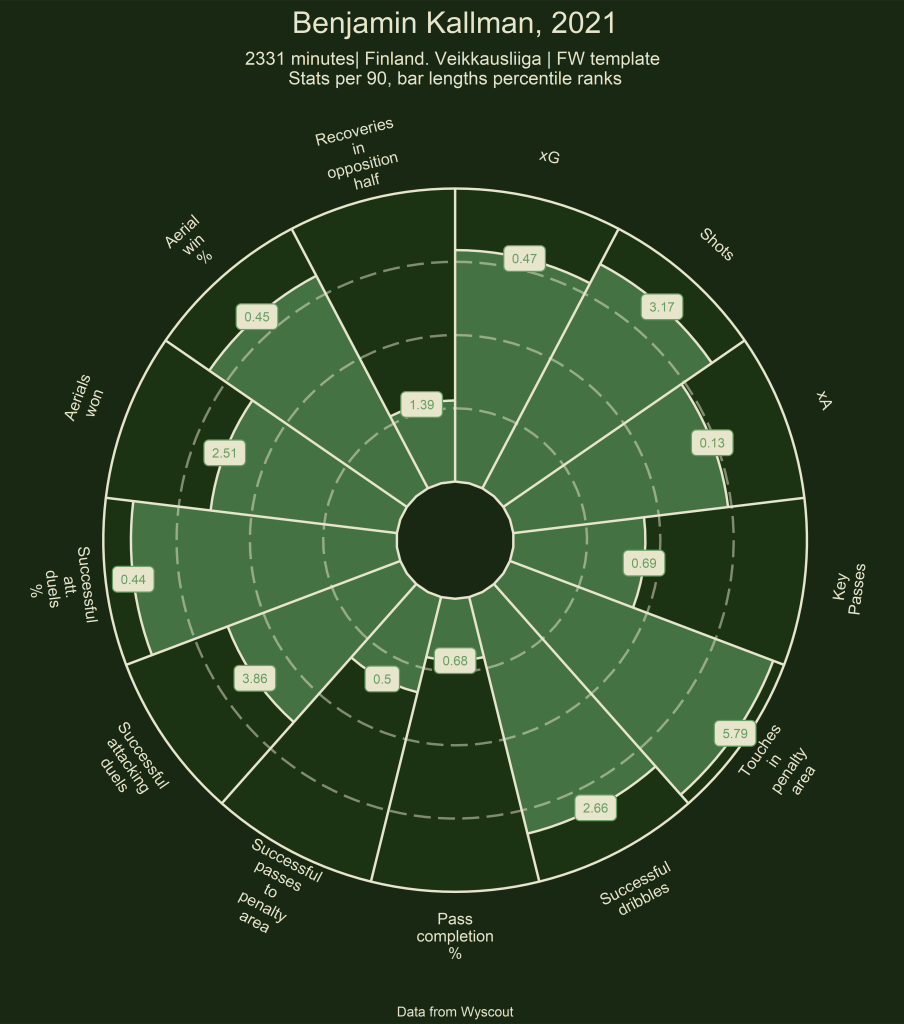

Inter have lost their overall most important player mid-season, as Benjamin Källman has moved to Cracovia in the Polish Ekstraklasa on a free transfer. This has been a known reality for Inter for a longer period of time, as he was never going to extend his contract, and there have been suitors after him since a year back. He was the top scorer in the league in 2021, and had continued in a similar vein of form in 2022. Let’s have a look at how his 2021 looked in terms of numbers.

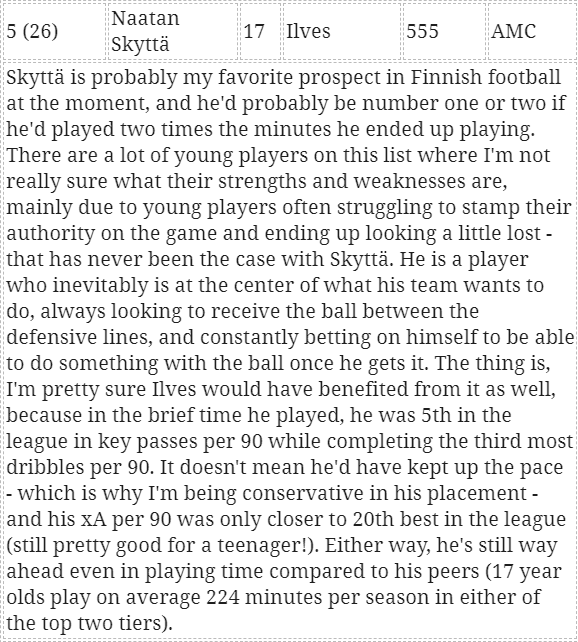

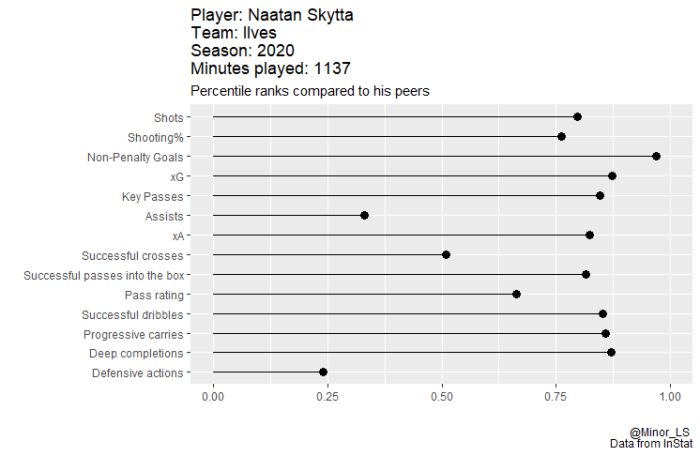

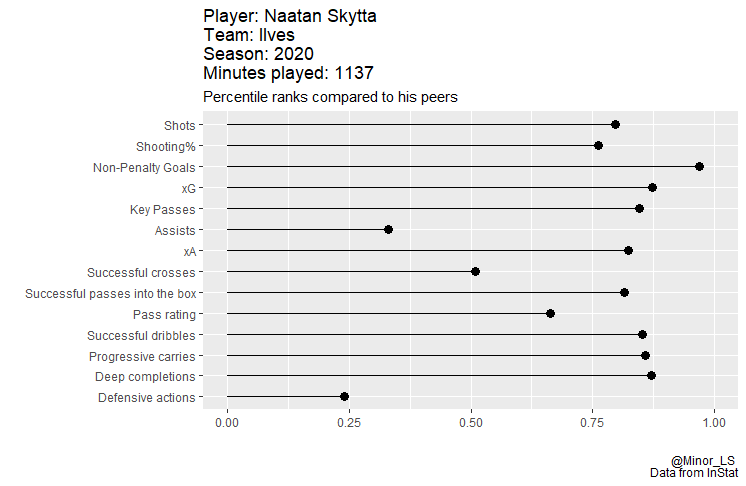

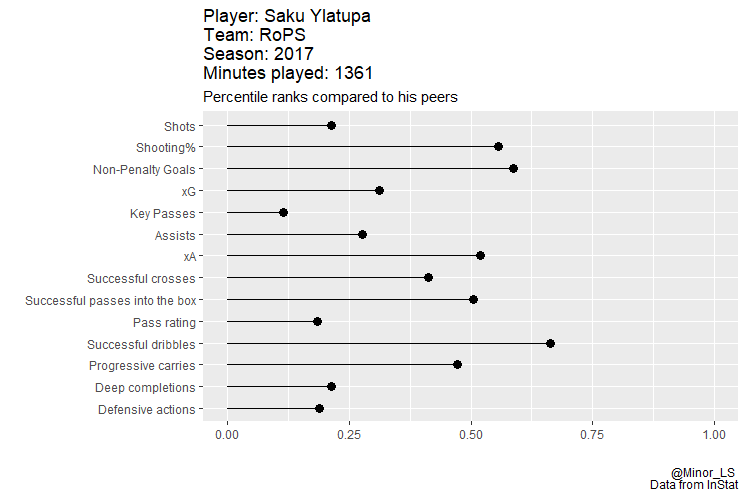

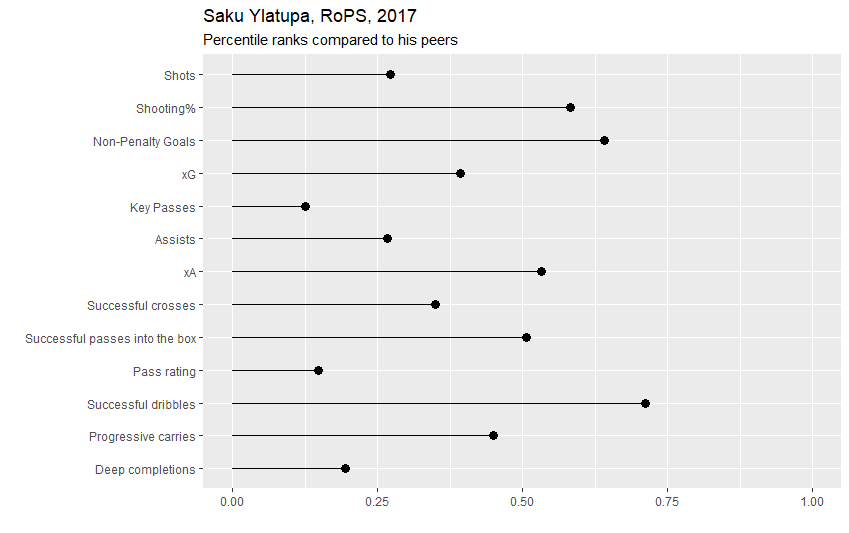

The pizza graph is a visualization that started to gain traction a couple of years ago when some prominent football analytics people started using them, most notably maybe Tom Worville over at the Athletic. The format really started to proliferate about a year ago, when a tutorial post with code popped up, and now it’s maybe the most widely used player comparison graphic out there.

Basically, the way to interpret the chart, is for each slice, the higher the colored bar, the better the player has performed in that statistic. The dotted lines represent percentile rank thresholds – if the bar is higher than the first dotted line, he performs better in that statistic than 25% of the sample, the next one represents 50% and the furthest one out represents 75%. The label at the end of the bar is the numerical value of that statistic per 90 (or if it is a rate state, the rate), so Källman took 3.17 shots per 90 and had a pass completion rate of 68%. The sample for each template is based on the most usual position the players in the sample has played in any particular season, which is then categorised into one of five positional categories (Forward, Central midfielder, Fullback, Central Defender and Goalkeeper). So for this graph, we can state that Källman got more touches in the opposition box in 2021 than almost all forward playerseasons in the sample.

In 2021, after having come back to Inter after a failed foray abroad midway through the 2020 season, Källman played his most consistent season, showing the same major skill he broke onto the scene with: the ability to consistently get shots from good locations. His years abroad, however, had allowed him to supplement his skillset – now, he was also creating shots for himself by dribbling, as well as winning aerial duels. After years playing as a center forward, he was mostly deployed on the right wing, in a role that seemed tailor-made to put him in positions where he could deploy his pace and power most effectively.

In 2022, Källman has largely picked up where he left off, this time back in his favored central position – this also shows in his playing style, as he shoots and dribbles less, while winning fewer aerial duels.

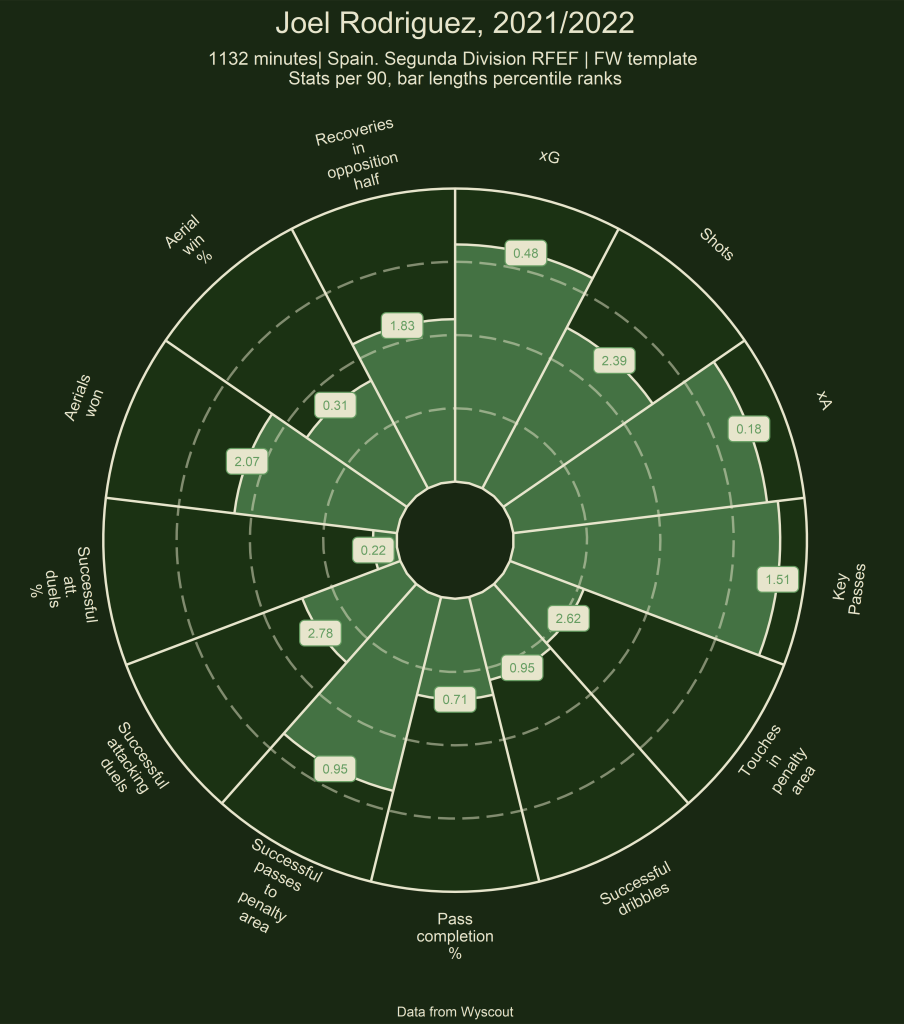

To replace him, Inter have signed two players Joel Rodriguez, a 23-year old who arrived from the Spanish fourth tier, and Tobias Fagerström, who has moved back to Finland after having spent several years in the Hamburger SV system.

Rodriguez, in terms of profile, looks sort of similar to Källman in 2022. Not a massive amount of shots, but generally from good locations. He seems to lack some of the secondary skills that Källman has, though, with quite few dribbles and being poor in duels. He does, however, have good creative numbers to make up the difference. Note that Wyscout only have a limited sample of Spanish 4th tier games covered, so in terms of minutes played, the sample shown is roughly half of the minutes he played that season according to Transfermarkt.

Fagerström hasn’t played a lot for a while, his closest season of a decent sample size goes all the way back to 2018/2019 in the German fourth tier. During that season, his stats are quite reminiscent of his older brother John. Good shot locations, but too few shots. Good creative numbers, but nothing much else to speak of. This is quite a long time ago, obviously, so there is good reason to have higher expectations, but if the profile is anything to go by, if you squint, it looks sort of similar to Källman in 2022.

Jair Tavares Da Silva had made a name for himself as one of the most dynamic midfielders in the Finnish league, before it became clear that he was something else altogether. HJK acted swiftly when it came to light that he had sexually abused a 12-year old, and ended his contract then and there. That naturally left a hole in HJK’s squad, a hole that has yet to be filled.

Tavares was especially known for his abilities going forward. Although he could play in a variety of central midfield roles, he seemed to always have a knack for getting in or around the box, and making actions that affected the outcome of the game. Although HJK are yet to sign a replacement, there have been rumors of a contract offer for Dutch free agent midfielder Pelle Clement.

Clement does seem to tick a lot of the same boxes as Tavares, with maybe slightly less impact in the attacking box, and more risky passing offset by better strength in duels, he looks like an enticing alternative – especially considering these performances were in the Dutch Eredivisie. The only major question mark is the same as it always is: what good reason could there be for a good peak-age player to come to Finland?

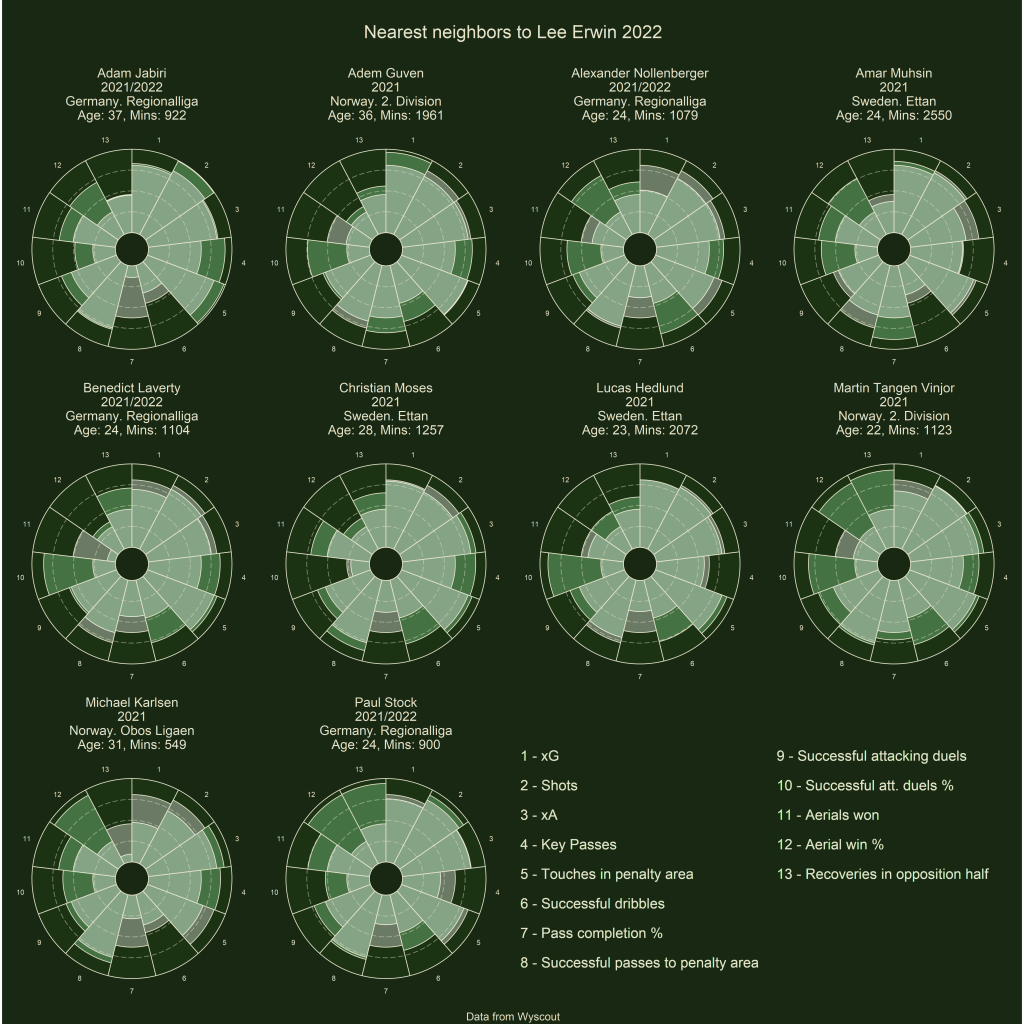

One of this season’s sensations has been Lee Erwin of Haka, the current leading goalscorer in the league. His form has been so good, in fact, that there were rumors of a six figure bid from a Turkish club only a couple of weeks ago. Six figures! For a 28-year old! I think it’s fair to say that Haka won’t have planned for the possibility of selling Erwin, so if the bid was indeed made, it is understandable why they would have rejected it.

Erwin, much like Källman, is supremely good at getting shots from good locations. He isn’t particularly good at recovering the ball in the opposition half, and is surprisingly poor in aerials, but does just about everything else you’d want from a center forward to a very good degree. Since there has been no talk of accepting the bid for him, there has also been no speculation on a replacement.

The three above scenarios represent different situations that have come up during this season, where teams in the Veikkausliiga have found themselves needing to activate themselves in the transfer market. They are also good representations of the certain stereotypes of needs that tend to arise: sometimes, you know beforehand that you’re going to have to find a replacement mid-season; sometimes something completely unexpected happens, and you’ll have to act fast; sometimes an opportunity arises from nowhere. Being prepared to act on these scenarios is critical when building a squad, as not everything will always go as planned, and being alert to opportunities can sometimes be what allows you to speculate on players – as with all commerce, the key is to sell high and buy low.

This is where data can be very helpful. Having a good approximation of what a player is doing for your team can give you a decent baseline when looking for alternatives on the market. There will always be contextual effects that skews the data this way and that, but that is true whether you dive deeply into the data or just dip your toes in it. Either way, looking at what you’re trying to replace is a good starting point.

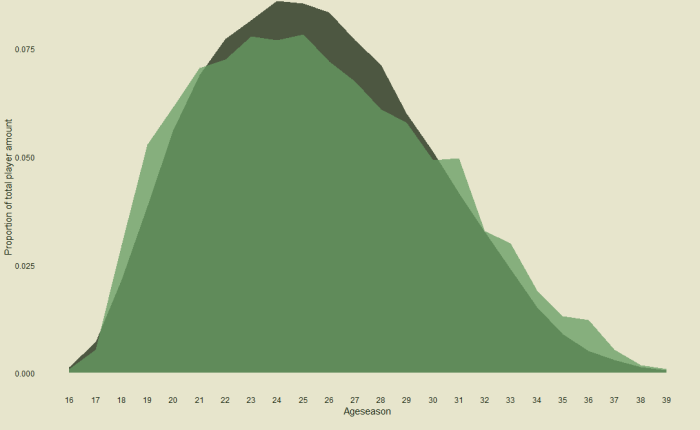

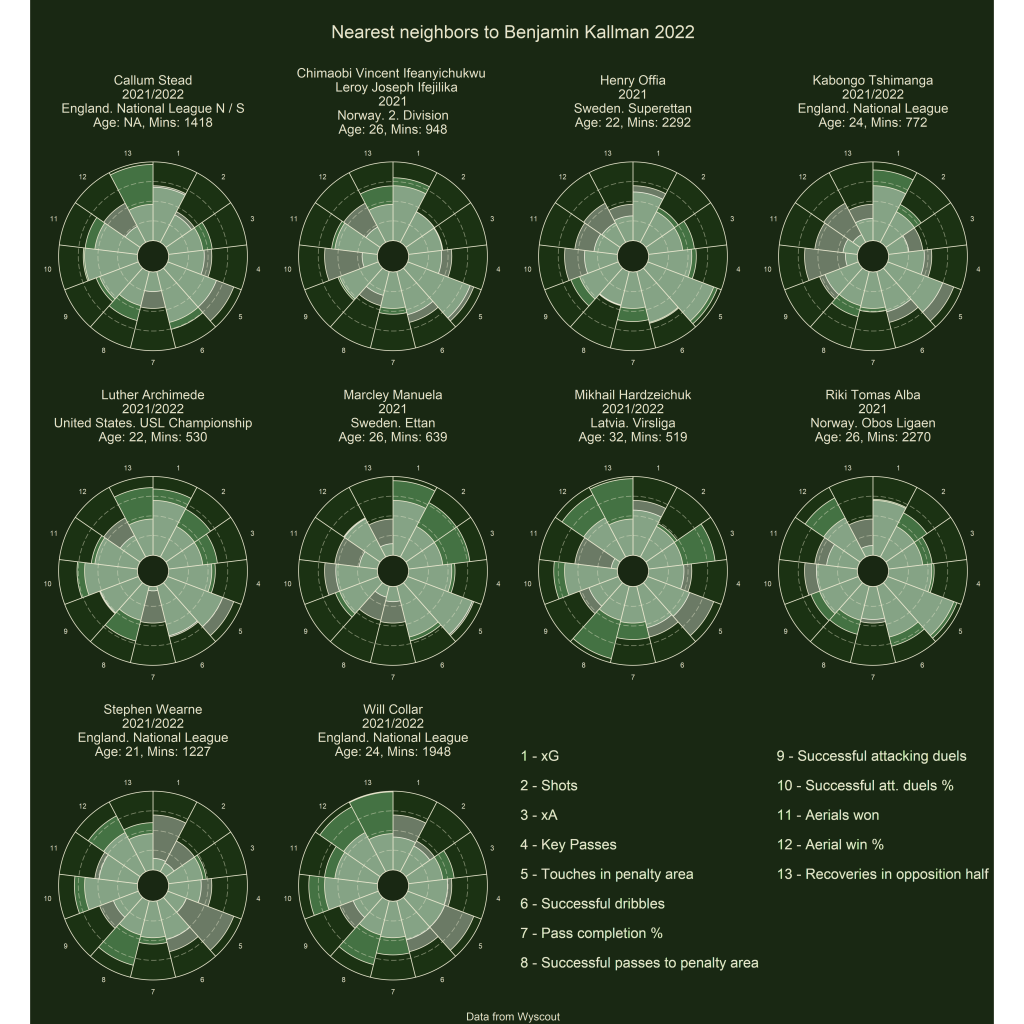

After you’ve established your baseline, you’re faced with wading through your data to find players who fit the bill. A popular method for doing this is using different kinds of nearest neighbor analyses. I’m no mathematician, so I couldn’t begin to explain the differences between them but I tend to use something called Mahalanobis distance, which is basically a multivariate way of calculating similarity between different sets of variables. Essentially, in our case, you feed the algorithm one player’s data, and give it a sample of players to compare against, and it produces a measure for how closely they match. This way, we can run through a large sample of data to find players who do roughly the same things as the player we are looking to replace, in basically no time.

We can also help the model out by reducing the sample. For example, we already know which leagues we are interested in. We also want to make sure the players have a big enough, and recent enough, sample to make it relevant to us. Another way of honing the model is by being more selective in the data we feed it. Since the algorithm is trying to find as close a match as possible, if you just feed it the data indiscriminately, it’s going to think that you are as interested in finding players with similar weaknesses as you are of finding players with similar strengths, so it makes sense to limit the measures we feed it. In this case, I’ve decided to only use the player’s top 6 measures by percentile rank (among the measures chosen for the pizza template in question).

In the case of Benjamin Källman, it would look something like this:

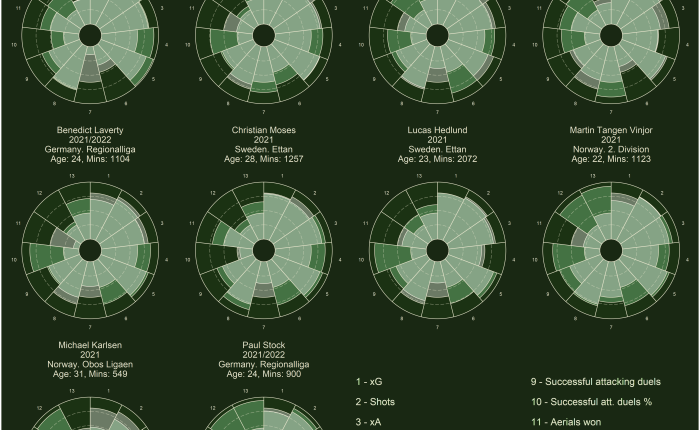

Above are the plots of the ten nearest neighbors to Benjamin Källman 2021 from the previously mentioned leagues, overlayed with Källman’s 2021 Veikkausliiga plot. I recommend spending a little while interpreting the graph because it is quite dense with information – essentially, each slice of pizza has two colors overlayed, green for the player in question, and white for the player we’re comparing to, in this case Källman. The portion of the slice that is white, is overlap between the players, the portion that is grey, is Källman being better than the other player, the portion that is green is the player being better than Källman.

Overall, I like the look of Nick van Staveren the most, while also being intrigued by the Regionalliga players and Jamie McGonigle. Macauley Longstaff has just moved to Notts County, so he wouldn’t be an alternative. Sung-Yoon Lee looks particularly interesting but he carries a massive sample size warning. Let’s also have a look at 2022.

If we’re looking for a 2022 replica of Källman, Marcley Manuela would be an interesting free agent pick-up, while Luther Archimede could be a decent gamble as his contract is up in November. Henry Offia and Riki Tomas Alba would probably be surer bets, but they probably have their eyes on an Allsvenskan/Eliteserien gig.

In the Källman example, we’re extremely late – some of the players have already moved while all of this data existed already in late May. When it comes to player recruitment, timing is of the essence, and as we’ve known for a while that Källman was leaving, this could have been a continuous process throughout the spring. Especially in combination with detailed video scouting, I think it could have been a fruitful exercise in Inter’s search for a replacement, and time will tell whether Inter got it right with the choices they made.

In the case of Tavares there are also some interesting options.

My eye is immediately drawn to Motoki Hasegawa and Ryotaro Ito, as very similar profile players (incidentally, it looks like both of their contracts are up this January). Christopher Scott is a good example of the dangers of this approach, as he put up the numbers above for… Bayern II, so he’s off the board. Deocleciano looks like the typical Latvian scheme to move a player forward so I don’t think we’re interested even if the player looks decent. The same goes for Gabriel Ramos Da Penha, and he looks to be a winger in any case. Laurent Kissiedou could be interesting, and his contract is up in November.

Realistically, I think a team like HJK could probably do a deal for either of the two Japanese players or Kissiedou, if there was mutual interest. It would very likely require an outlay from the club, and the player’s wages would probably be quite high from a Finnish baseline, but the profile of player would be exactly what a team like HJK should be looking for: young but not too young, on a short contract, with a point to prove in Europe, and recent history of excellence elsewhere. With some strong performances in continental qualifiers, the financial side of it could quickly start to look like an afterthought.

Let’s, finally, have a look at Erwin:

We’re looking for a quick buy that would allow us to earn a profit on the sale of Erwin while keeping us competitive, so Christian Moses is out of the question as he has moved to IFK Värnamo in the Allsvenskan. I’m also not sure about Jabiri, Guven and Karlsen due to their respective ages. Nollenberger plays. 3. Bundesliga nowadays, Muhsin is one of the top goalscorers in Superettan, Vinjor is listed as a central midfielder by Transfermarkt and is putting up strong performances in the second tier of Norway. This leaves us with Benedict Laverty, who is listed as a left winger but looks like he could be potentially gettable, Lucas Hedlund, who hasn’t played a lot, but has scored when he has, in Superettan this season, and Paul Stock, who in fairness looks the most similar to Erwin of the above bunch.

It’s difficult to know for sure, but I’m not unconvinced that one of these players could be bought for a high five figures, low six figures offer – another question is whether they would want to join. I’d also consider it quite likely that the performances would translate to the Veikkausliiga, at least to the extent that the players would be productive, if not re-saleable.

Squad building isn’t as easy as just arranging some number from best to worst and picking whomever is highest, but I’d also argue that it doesn’t have to be the kind of 4D chess it is made out to be at times. By allowing the data to suggest players for you, one can rid oneself of some of the biases that influence decision making, and – more importantly – take control of the talent identification process, which for many teams is led by people with severe conflicts of interest. It can also allow you to focus your scouting from larger areas to specific players in local markets, helping you to target only the type of player worth spending time on.

The point isn’t to claim to have some silver bullet to solve all transfer woes – no matter how good the talent identification is, the bigger problem will always be to convince players to make the move to a league that is far from glamorous. However, even with the limited amount of inside knowledge I have about the inner workings of Veikkausliiga transfers, implementing something like the above, by my estimate, would have the potential to improve squad building decision making quite significantly, for basically no cost.

I have a third part of this series lined up, but won’t reveal any details until I get it researched and written, in the meantime, follow me on Twitter for future updates!